Chapter 6

A Quagmire of Evasion

The major problem with discussions about free will is that philosophers have put forward a heap of definitions that have nothing to do with what no philosophers think free will means. I am tempted to write "normal people" as opposed to "philosophers," but maybe that's a little uncharitable. And I don't want to be uncharitable. Certainly not.

For this reason, let me begin by stating the problem without using the term free will. The currently established laws of nature are deterministic with a random element from quantum mechanics. This means the future is fixed, except for occasional quantum events that we can-not influence. Chaos theory changes nothing about this. Chaotic laws are still deterministic; they are just difficult to predict, because what happens depends very sensitively on the initial conditions (butterfly flaps and all that).

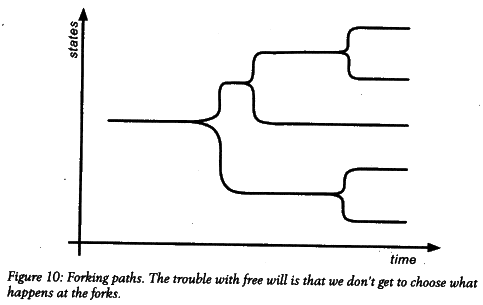

Our life is thus not, in Jorge Luis Borges's words, a "garden of forking paths" where each path corresponds to a possible future and it is up to us which path becomes reality (figure 10). The laws of nature just don't work that way. For the most part, there is really only OnePath, because quantum effects rarely manifest themselves macroscopically. What you do today follows from the state of the universe yesterday, which follows from the state of the universe last Wednesday, and so on, all the way back to the Big Bang.

But sometimes random quantum events do make a big difference in our lives. Remember the researcher who might get into a highway accident depending on where a particle appeared on her screen? The paths do fork every once in a while, but we have no say in it. Quan-tum events are fundamentally random and not influenced by any-thing, certainly not by our thoughts.

As promised, I didn't use the term free will to lay out the situation. Let’s then discuss what it means that the future is fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence.

Personally, I would just say this means free will does not exist and put the case to rest. I feel encouraged in that because free will itself Isan inconsistent idea, as a lot of people wiser than 1 am have pointed out before. For your will to be free, it shouldn't be caused by anything else. But if it wasn't caused by anything-if it's an "uncaused cause, “as Friedrich Nietzsche put it-then it wasn't caused by you, regardless of just what you mean by you. As Nietzsche summed it up, it's "the best self-contradiction that has been conceived so far." I'm with Nietzsche.

This is how I think about what's going on instead: our brains perform computations on input, following equations that act on an initial state. Whether these computations are algorithmic is an open question that we'll come to later, but there's no magic juice in our neocortex that puts us above the laws of nature. All we're doing is evaluating what are the best decisions to make given the limited information we have. A decision is the result of our evaluation; it does not require anything beyond the laws of nature. My phone makes decisions each time it calculates what notifications to put on the lockscreen; clearly, making decisions does not necessitate free will.

We could have long discussions about just what it means that a decision is "the best," but that's not a question for physics, so let us leave it aside. Point is, we are evaluating input and trying to optimize our lives using some criteria that are partly learned and partly hard-wired in our brains. No more, and no less. And none of this conclusion depends on neurobiology. It is still unclear how much of our decision-making is conscious and how much is influenced by subconscious brain processes, but just how the division into conscious and subconscious works is irrelevant for the question whether the out-come was determined.

If free will doesn't make sense, why, then, do many people feel it describes how they go about their evaluations? Because we don’t know the result of our thinking before, we are done; otherwise, we wouldn’t have to do the thinking. As Ludwig Wittgenstein put it, “The freedom of the will consists in the fact that future actions can-not be known now." His Tractatus is now a century old, so it's not like this is breaking news.

Case settled? Of course not. Because one can certainly go and define something and then call it free will. This is the philosophy of compatibilism, which has it that free will is compatible with determinism, never mind that-just to remind you-the future is fixed except for the occasional quantum event that we cannot influence. Among philosophers, compatibilists are currently the dominant camp. In a 2009 survey carried out among professional philosophers, 59 percent identified as compatibilists.

The second biggest camp among philosophers are libertarians, who argue that free will is incompatible with determinism, but that, because free will exists, determinism must be false. I will not discuss libertarianism because, well, it's incompatible with what we know about nature.

Let us therefore talk a little more about compatibilism, the philosophy that Immanuel Kant charmingly characterized as a "wretched subterfuge," that the nineteenth-century philosopher William James put down as a "quagmire of evasion," and that the contemporary phi-looper Wallace Matson called out as "the most flabbergasting in-stance of the fallacy of changing the subject." Yes, indeed, how do you get free will to be compatible with the laws of nature, keeping in mind that-let's not forget-the future is fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence?

One thing you can do to help your argument is to improve physics little bit. The philosopher John Martin Fischer has dubbed philosophers who do this "multiple-past compatibilists" and "local-miracle compatibilists." The former argue that your actions change the past to something that it wasn't. The latter argue that supernatural events beyond the laws of nature allow your decision to somehow avoid the predictions of theories that have been confirmed countless times. I will not discuss these here either, because this is a book about what we can learn from physics, not about how we can creatively ignore physics.

Among the compatibilist ideas that are at least not wrong, the most popular one is that your will is free because it's not predictable, certainly not in practice and possibly not even in principle. This position is maybe most prominently represented by Daniel Dennett. If you want to think about free will that way, fine. But the future is still fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence.

The philosopher Jenna Ismael has furthermore argued that freewill is a property of autonomous systems. By this she means that different subsystems of the universe differ in how much their behavior depends on external input versus internal calculation. A toaster, for example, has very little autonomy-you push a button and it reacts. Humans have a lot of autonomy because their deliberations can proceed mostly decoupled from external input. If you want to call that free will, fine. But the future is still fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence.

There are quite a few physicists who have backed compatibilism by finding niches in which to embed free will into the laws of nature. Sean Carroll and Carlo Rovelo suggest that we should interpret freewill as an emergent property of a system. A pepped-up version of this argument was recently put forward by Philip Ball. It relies on using causal relations between macroscopic concepts-so also emergent properties-to define free will.

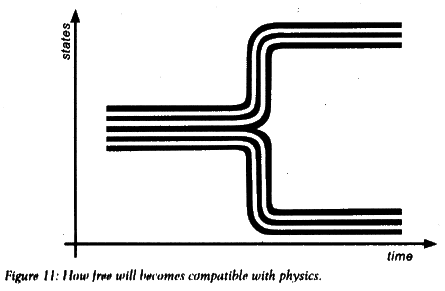

Remember that emergent properties are those that arise in ap-proximate descriptions on large scales when details of the microphysics have been averaged. Figure 11 illustrates how this can be used to make place for free will. On the microscopic level, the paths (white lines) are determined by the initial value-that is, the place they start from on the left. But on the macroscopic level, if you forget about the exact initial conditions and look at the collection of all microscopic paths, the macroscopic path (black outline) forks.

The above-mentioned physicists now say that if you ignore the determined behavior of particles on the microscopic level, then youkan no longer make predictions on the macroscopic level. The paths fork: hurray! Of course, this happens just because you've ignored what’s really going on. Yeah, you can do that. But the future is still fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence. When Sean Carroll summed up his compatibilist stance with "freewill is as real as a baseball," he should have added "and equally free."

Having said that, I don't have a big problem with physicists' or philosophers' compatibilist definitions of free will. After all, they’re just definitions, neither right nor wrong, merely more or less useful. But I don't think such verbal acrobatics address the issue that normal people-sorry, I mean no philosophers-worry about. A 2019 survey of more than five thousand participants from twenty-one countries found that "across cultures, participants exhibiting greater cognitive reflection were more likely to view free will as incompatible with causal determinism." It seems we weren't born to be compatibilists. That’s why, for many of us, learning physics shakes up our belief in what we think of as free will-as it did for me. This, in my mind, is the issue that needs to be addressed.

As you see, it isn't easy to make sense of free will while respecting the laws of nature. Fundamentally, the problem is that, for all we cur- -gently know, strong emergence isn't possible. That means all higher-level properties of a system-those on large scales-derive from the lower levels where we use particle physics. Hence, it doesn't matter just how you define free will; it'll still derive from the microscopic behavior of particles-because everything does.

The only way I can see to make sense of free will is therefore that the derivation from the microscopic theory fails for some cases for some reason. Then strong emergence could be an actual property of nature and we could have macroscopic phenomena-free will among them-that are truly independent of the microphysics. We don't now have a shred of evidence that this indeed happens, but it's interesting to think about what it would take.

To begin with, the mathematical techniques we use to solve the equations that relate microscopic with macroscopic laws don't always work. They often rely on certain approximations, and when those approximations aren't adequate to describe the system of interest, we just don't know what to do with the equations. This is a practical problem, for sure, but it doesn't matter insofar as the properties of the laws are concerned. The relation between the deeper and higher levels doesn't go away just because we don't know how to solve the equations that relate them.

What gets us a little closer to strong emergence are two examples where physicists have studied the question whether composite systems can have properties whose value is undecidable for a computer. If that were so, that would be a much better argument for a macro-scope phenomenon that is "free" of the microphysics than just saying we don't know how to compute it. It'd actually prove that it can't be computed. But these two examples require infinitely large systems for the argument to work. The statement then comes down to saying that for an infinitely large system, certain properties cannot be calculated on a classical computer in finite time. It's not a situation we’d encounter in reality and, hence, it doesn't help with free will.

However, it could be that the derivation of the macroscopic behavior from the microphysics fails for another reason. It could be that in the calculation we run into a singularity beyond which we just cannot continue-neither in practice nor in principle. This does not necessarily bring back infinites again, for in mathematics a singular point is not always associated with something becoming infinite; it's just appointed where a function can't be continued.

We currently have no reason to think this happens for the actual microphysics that is realized in our universe, but it's something that could conceivably turn out to be so when we understand the math better. So if you want to believe in a free will that's truly governed by natural laws independent from those of elementary particles, the possibility that the derivation of the microphysical laws runs into a sin-gular point seems to me the most reasonable one. It's a long shot, but it’s compatible with all we currently know.

Life without Free Will

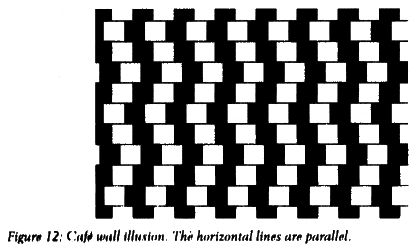

The American science writer John Horgan calls me a "free will de-Nier," and by now you probably understand why. But I certainly do not deny that many humans have the impression they have free will. We also, however, have the impression that the present moment is special, which we already saw is an illusion, and if I went by my impression, I'd say the horizontal lines in figure 12 aren't parallel. If my research in the foundations of physics has taught me one thing, it’s that one shouldn't count on personal impressions. It takes more than an impression to infer how nature really works.

Despite the limitations of our brains, not to brag, but I think we humans have done a pretty good job figuring out the laws of nature. We did, after all, come to understand that "now" is an illusion, and, using your brain at its finest, you can go and measure the lines in figure 12 to convince yourself they really are parallel. They still won’t look parallel, but you will know they're parallel nevertheless. I think we should deal with free will the same way: leave aside our intuitive feelings and instead follow reason to its conclusions. You will still feel if you have free will, but you will know that really, you're running sophisticated computation on your neural processor.

But I'm not trying to missionize you. As I said, it all depends on how you define free will. If you prefer a compatibilist definition of freewill and want to continue using the term, science says nothing against that. Therefore, to answer this chapter's question: Has physics ruled out free will? No, it has merely ruled out certain ideas about free will. Because for all we currently know the future is fixed except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence.

How can we deal with this? I get asked this a lot. It seems to me the problem is that many of us grow up with intuitive ideas about how our own decision-making works, and when these naive ideas run into conflict with what we learn about physics, we have to readjust our self-image. This isn't all that easy. But there are a few ways to sort it out.

The easiest way to deal with it is through dualism, according to which the mind has a nonphysical component. Using dualism, youkan treat free will as a scientific concept, a property of your soul, if you wish. This will be compatible with physics as long as the non-physical component does not interact with the physical one, because then it'd be in conflict with evidence-it'd become physical. Because the physical part of our brain is demonstrably the thing we use to make decisions, I don't see what one gains from believing in a non-physical free will, but then this isn't a new problem with dualism, and at least it isn't wrong.

You are also welcome to use the little loophole in the derivation from microphysics that I detailed earlier. Though I suspect if you tell someone you think free will is real because the renormalization group equations might run into an essential singularity, you might as well paint GEEK on your forehead.

Personally, I think the best way to deal with the impossibility of changing the future is to shift the way we think about our role in the history of the universe. Free will or not, we are here, and therefore we matter. But whether ours will be a happy story or a sad story, whether our civilization will flourish or wither, whether we will be remembered or forgotten-we don't yet know. Instead of thinking of our-selves as selecting possible futures, I suggest we remain curious about what’s to come and strive to learn more about ourselves and the unit-verse we inhabit.

I have found that abandoning the idea of free will has changed the way I think about my own thinking. I have begun paying more attention to what we know about the shortcomings of human cognition, logical fallacies, and biases. Realizing that in the end I am just working away on the input I collect; I have become more selective and careful with what I read and listen to.

Odd as this may sound, in some circumstances I've had to work hard to convince myself to listen to myself. For example, I commuted for several years between Germany and Sweden, racking up dozens of flights a year. Yet for some reason it didn't occur to me to sign up fora frequent flyer card. When someone asked me about it two years into my commute, I felt rather dumb. But instead of immediately signing up for a frequent flyer card, I put it off, reasoning that I'd forgone so many benefits already, I might as well not bother. It's a curious in-stance of loss aversion ("throwing good money after bad"), though in this case it wasn't an actual loss but an absence of benefits. Recognizing this, I did eventually sign up for a card. If I hadn't known it was a cognitive bias, I don't think I would have; I'd instead have done my best to forget about it altogether, thereby working against my own interests.

I am not telling you this because I'm proud I made a rational decision (in this instance, at least). To the very contrary, I am telling you this to highlight that I'm as irrational as everybody else. Yet I think I have benefited from accepting that my brain is a machine-a sophisticated machine, all right, but still prone to error-and it helps to know which tasks it struggles with.

When I explain that I don't believe in free will, most people will joke that I couldn't have done otherwise. If you had this joke on your mind, it's worth contemplating why it was easy to predict.

Free Will and Morals

On January 13, 2021, Lisa Marie Montgomery became the fourth woman to be executed in the United States, the first in sixty-seven years. She was sentenced to death for the murder of Bobbie Jo Stinnett, age twenty-three and, at the time of the crime, eight months pregnant. In 2004, Montgomery befriended the younger woman. On December 16 of that year, she visited Stinnett and strangled her. Then she cut the unborn child from the pregnant woman's womb. For a few days, Montgomery pretended the child was hers, but she confessed quickly when charged by police. The newborn remained unharmed and was returned to the father.

Why would someone commit a crime as cruel and pointless as this? A look at Montgomery's life is eye-opening.

According to her lawyers, Montgomery was physically abused by her mother from childhood on. Beginning at age thirteen, she was regularly raped by her stepfather-an alcoholic-and his friends. She repeatedly, but unsuccessfully, sought help from authorities. Mont-Gomery married young, at the age of eighteen. Her first husband, with whom she had four children, also physically assaulted her. By the time of the crime, she had been sterilized, but sometimes pretended to be pregnant again. Once in prison, Montgomery was diagnosed with whole list of mental health problems: "bipolar disorder, temporal lobe epilepsy, complex post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative dis-order, psychosis, traumatic brain injury and most likely fetal alcohol syndrome."

I would be surprised if the previous paragraph did not change your mind about Montgomery. Or, if you knew her story already, I would be surprised if you did not have a similar reaction the first time you heard it. The abuse she suffered at the hands of others doubtless con-tributed to the crime. It left a mark on Montgomery's psyche and personality that contributed to her actions. To what extent was she even responsible? Wasn't she herself a victim, failed by institutions that were supposed to help her, too deranged to be held accountable? Did she act out of her own free will?

We frequently associate free will with moral responsibility in this way, which is how it enters our discussions about politics, religion, crime, and punishment. Many of us also use free will as a reasoning device to evaluate personal questions of guilt, remorse, and blame. Infect, much of the debate about free will in the philosophical literature concerns not whether it exists in the first place but how it connects tumoral responsibility. The worry is that if free will goes out the window, society will fall apart because blaming the laws of nature is pointless.

I find this worry silly. If free will doesn't exist, it has never existed, so if moral responsibility has worked so far, why should it suddenly stop working just because we now understand physics better? It's not as though thunderstorms changed once we understood they're not Zeus throwing lightning bolts.

The philosophical discourse about moral responsibility therefore seems superfluous to me. It is easy enough to explain why we-as individuals and as societies-assign responsibility to people rather than to the laws of nature. We look for the best strategy to optimize our well-being. And trying to change the laws of nature is a bad strategy.

Again, one can debate just exactly what well-being means; the fact that we don't all agree on what it means is a major source of conflict. But just exactly what it is that our brains try to optimize, and what the difference is between your and my optimization, isn't the point here. The point is that you don't need to believe in free will to argue that locking away murderers’ benefits people who could potentially be murdered, whereas attempting to change the initial conditions of the universe doesn't benefit anyone. That's what it comes down to: We evaluate which actions are most likely to improve our lives in the future. And when it comes to that question, who cares whether philosophers have yet found a good way to define responsibility? If you are a problem, other people will take steps to solve that problem-they will "make you responsible" just because you embody a threat.

That way, we can rephrase any discussion about free will or moral responsibility without using those terms. For example, instead of questioning someone's free will, we can debate whether jail is really the most useful intervention. It may not always be. In some circum-stances, mental health care and preventions against family violence may be the. longer lever to reduce crime. And of course, there are other factors to consider, such as retaliation and deterrence and so on. This isn't the place to have this discussion. I merely mean to demon-strata that it can be had without referring to free will.

The same can be done for personal situations. Whenever you ask a question like "But could they have done differently?" you are evaluating the likelihood that it may happen again. If you come to the conclusion that it's unlikely to happen again (in terms of free, will you might say, “They had no other choice"), you may forgive them ("They were not responsible"). If you think it's likely to happen again ("They, did it on purpose"), you may avoid them in the future ("They were responsible"). But you can rephrase this discussion about moral responsibility in terms of an evaluation about your best strategy. You could, for ex-ample, reason: "They were late because of a flat tire. It's therefore unlikely to happen again, and if I was angry about it, I might lose good friends." Free will is utterly unnecessary for this.

Let me be clear that I don't want to tell you to stop referring to free will. If you find it's handy, by all means, continue. I just wanted to offer examples for how one can make moral judgments without it. This matters to me because I am somewhat offended by being cast amorally defunct just because I agree with Nietzsche that free will be an oxymoron.

The situation is not helped by the recurring claim that people who do not believe in free will are likelier to cheat or harm others. This view was expressed, for example, by Azim Shariff and Kathleen Voshon a 2014 Scientific American article in which they said their research shows that "the more people doubt free will, the more lenient they become toward those accused of crimes and the more willing they are to break the rules themselves and harm others to get what they want."

First, let us note that-as is often the case in psychology-other studies have given different results. For example, a 2017 study on freewill and moral behavior concluded, "We observed that disbelief in free will had a positive impact on the morality of decisions toward others." The question is the subject of ongoing research; the brief summary is that it's still unclear how belief in free will relates tumoral behavior.

More insightful is to look at how these studies were conducted in the first place. They usually work with two separate groups, one primed to doubt free will, the other one a neutral control group. Forth no-free-will priming, it has become common to use passages from Francis Crick's 1994 book, The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul. Here is an excerpt:

You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. Who you are is nothing but a pack of neurons.

This passage, however, does more than just neutrally inform people that the laws of nature are incompatible with free will. It also denigrates their sense of purpose and agency by using phrases like "no more than" and "nothing but." And it fails to remind the reader that this "vast assembly of nerve cells" can do some truly amazing things, like reading passages about itself, not to mention having found out what it's assembled of to begin with.

Of course, Crick's passage is deliberately sharply phrased to get his message across (not unlike some passages you read in chapter 4 of this very book); nothing wrong with that in and of itself. But it doesn’t prime people just to question free will; it primes them for fatalism-the idea that it doesn't matter what you do. Suppose he'd primed them instead using this passage:

You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are the result of a delicately interwoven assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. That pack of neurons is the product of billions of years of evolution. It endows you with an unparalleled ability to communicate and collaborate, and a capacity for rational thought superior to that of all other species.

Not as punchy as Crick's version, I admit, but I hope it illustrates what I mean. This version also informs readers that their thoughts and actions are entirely a result of neural activity. It does so, however, by emphasizing how remarkable our thinking abilities are. It would be interesting to see whether people primed in this way to disbelieve in free will are still more likely to cheat on tests, don't you think?

>> THE BRIEF ANSWER

According to the currently established laws of nature, the future is determined by the past, except for occasional quantum events that we cannot influence. Whether you take that to mean that free will does not exist depends on your definition of free will.

| ![]()